The colorful illustrations usually found in manuscript books are called "miniatures". The word is originated from 'miniatura' which means that is painted with sülüğen (red lead). In time, with the influence of the word minor, it also meets the meaning of small picture. In Islamic art, the miniature is called "tasvir" and the miniature artist is called "musavvir" or "nakkaş". Miniatures are either included in manuscripts to accompany the manuscript, or on a single leaf to be collected on albums. The basic materials are watercolor paint, gold and sometimes silver. Cultural, geographical and artistic differences arise in the Islamic miniatures that are designed in the form of compositions and unlike Western paintings that do not give three senses of feeling, lack perspective, and do not use light-shadow contrasts.

The writing and ruling miniatures of the period prior to the Turks' acceptance of Islam generally depicts the Uyghur princes and princesses and Mani and Uyghur priests. The style of these depictions, made in an environment where various cultures and religions are influential, are very rich and show regional differences.

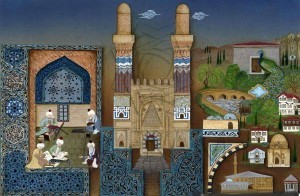

Other examples of the development of Turkish painting art until the 13th century unfortunately disappeared. Seljuks style miniatures which have Uyghur origin describe objects and scenes belonging to daily life in musavver (illustrated) manuscripts. Early miniature works produced in Anatolia are similar to contemporary paintings outside Anatolia; the handling of the depictions is realistic and have a narrative style. In the 13th century, artifacts depicted in technique and style were similar to the Far East and Chinese art are revealed during Ilkhanids period. During the Calayirs period, a superficial and decorative painting style is born and developed in later periods. Important examples of Islamic miniatures can be seen in handwritten manuscripts prepared under the auspices of the Timurids. In this period, cities such as Herat and Shiraz, where the works of increasing quantity and quality in the patronage the intellectual rulers and princes are produced, become centers of artistic schools. In the 14th and 15th century, The Karakoyunlu and Akkoyunlu Turkmen styles follow a similar production process; the arts proceeds with the support of the rulers. In the Safavid period, which is the contemporary of the Ottoman Empire, musavver manuscripts in both palace qualities are produced, and book production with miniatures activity in various cities such as Shiraz is developed as a trading arm. Uzbeks, Mughals, Qajars, also depicts art examples, stylistic differences are seen in the traditional understanding continues.

In the Ottoman period, art works are produced in the workshops organized under the "Ehl-i Hıref" organization. The main demand of the workshops where craftsmen and artists take part derived from the palace, therefore the sultan and the state administrators were biggest sponsors of the workshops. Some of the handwritten manuscripts belonging to the early Ottoman era are prepared in Edirne, the second capital city. After Istanbul became the capital, Turkmen style and Western art influences are seen in the first works produced here. Besides the works of the literary genre, the works on history start to be depicted. The artists and miniature books brought to Istanbul after the campaigns of Selim I (1512-1520) provided a hybrid style.

Matrakçı Nasuh is a striking artist with topographic city paintings during the period of Suleyman I. He worked on some history books along with the poets titled "Şehnâmeci", which is assigned to write works describing the Ottoman history, and these are adorned with many illustrations accompanying the manuscript. The authentic Ottoman iconography created by Nakkaş Osman became the dominant painting style. In the classical Ottoman style seen from the second half of the 16th century, abundantly embroidered surface decoration leaves its place to simple backgrounds and compositions. These depictions, in which the image-text relation can be established clearly, shed light on the Ottoman sultanate, the palace protocol, the city life, the military events and deviate from its contemporaries with its documentary characteristics. Nakkaş Osman's sultan portraits are also a model in the depictions of the Ottoman sultans. Nakkaş Hasan Pasha, a successor, despite having an authentic style of his own, mainly followed the Nakkaş Osman’s depiction style. In this period, depicted books are also produced in the provinces apart from the palace.

17th century murakka' (album) production becomes important; also large-sized single-leaf depictions are made. Apart from the works on history, literature, astronomy, fortune telling and apparel are also frequently seen in the albums. The last glorious examples of Ottoman miniature art are given by Nakkaş Levni and Abdullah Buhari in the 18th century. After printing house became widespread and Western depiction values like perspective, light-shadow and realistic figures became popular, the traditional Ottoman miniature started to disappear.

Today, traces of old styles and modern interpretations can be found in the contemporary miniature painting which is performed with traditional methods.